Browse Exhibits (70 total)

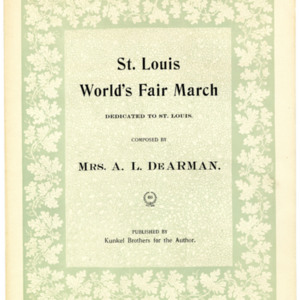

Class, Race, & Sheet Music at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

In 1904, the city of St. Louis, Missouri hosted the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, a world’s fair commemorating the Purchase and celebrating the world-changing idealism, energy, and ingenuity of the United States. While marking the nation’s economic and geographic expansion, the Exposition’s presentation of the United States as Europe’s cultural heir struggled to balance elite, Euro-centric cultural values with the expanding relevance of a popular culture partially rooted in non-white traditions.

Gaylord Music Library’s collection of sheet music from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition demonstrates how the intersecting values of education and entertainment, high and low culture, class and race played out in the musical publications surrounding the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Three Musical Styles explains the various kinds of sheet music available in the U.S.A. at the turn-of-the-century.

How can sheet music explain popular culture? Westward Expansion presents Neil Moret's march, A Deed of the Pen, as a multimedia commemoration of the Louisiana Purchase.

Education and Entertainment intermingled at the Exposition. Learn how the fair's sheet music demonstrated the appeal of non-white music as a source of entertainment, even though European traditions were still prized as the source of intellectual ingenuity.

Exposition sheet music was full of references to European culture, particularly pieces published in St. Louis. Read about these European Ambitions here.

White Popular Culture included certain stock figures who appear all over Exposition-themed songs and stories.

While the Exposition was not officially a segregated event, Jim Crow laws made it difficult for African American patrons to participate fully in the fair. Even so, Black Popular Culture (and white imitations of it) contributed significantly to the Exposition's sheet music production.

About the recordings featured in this exhibit:

Wherever possible, we have provided links to period recordings, so that you can hear the music as it was performed by early twentieth century artists.

Period recordings are not available for all of the pieces. An Innovation Grant from the Washington University Libraries funded a live recital of music from the Exposition in November 2016. These performances by student and local musicians were recorded for this exhibit. Washington University makes these recordings available to the public under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Please do not distribute them without crediting this exhibit and the performers.

For questions or concerns, please contact music@wumail.wustl.edu

Last update: 03/03/2021

Connecting Contexts: the Modern Literature Collection and The Letters of Samuel Beckett

This exhibit spotlights manuscript materials and published texts from the University Libraries’ Modern Literature Collection (MLC), one of the foremost Beckett repositories in the world. It connects these materials with information and excerpts from The Letters of Samuel Beckett, the first comprehensive edition of Beckett’s letters.

Joel Minor, curator of the MLC, organized the exhibit with Lois Overbeck, co-editor of The Letters of Samuel Beckett and director of the Letters of Samuel Beckett Project at Emory University. The onsite exhibit, upon which this digital exhibit is based, was on view July-December 2019 in the Ginkgo Room of John M. Olin Library.

The multi-faceted colloquium, "What is the Word: Celebrating Samuel Beckett" was held at Olin Library and Mallinckrodt Center at Washington University, November 7-8, 2019. You can see the full list of speakers and abstracts here and read a summary of each day's activities on our blog. Videos of many of the talks are on our YouTube Channel.

A smaller Beckett exhibit, curated by graduate student Kyle Young, coincided with Connecting Contexts and is also now a digital exhibit, called "If you could finish it..." : Beckett's Revisions and Autotranslations.

Depicting Devotion

Designed to introduce the viewer to the illuminations that accompany the essential texts found in Books of Hours.

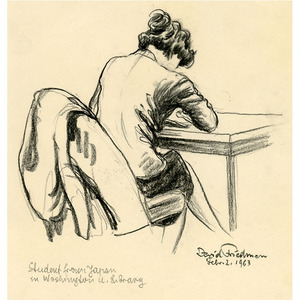

Enjoyment In Libraries With The Candid Pencil of David Friedman

Enjoyment in Libraries features sketches of patrons in St. Louis area libraries, drawn by David Friedman during the 1960s.

F.B. Eyes Digital Archive: FBI Files on African American Authors and Literary Institutions Obtained Through the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

Few institutions seem more opposed than African American literature and J. Edgar Hoover's white-bread Federal Bureau of Investigation. But behind the scenes the FBI's hostility to black protest was energized by fear of and respect for black writing. Drawing on thousands of pages of recently released FBI files, William J. Maxwell’s book F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature exposes the Bureau's intimate policing of five decades of African American poems, plays, essays, and novels. Starting in 1919, year one of Harlem's renaissance and Hoover's career at the Bureau, secretive FBI "ghostreaders" monitored the latest developments in African American letters. By the time of Hoover's death in 1972, these ghostreaders knew enough to simulate a sinister black literature of their own. The official aim behind the Bureau's close reading was to anticipate political unrest. Yet, as F.B. Eyes reveals, FBI surveillance came to influence the creation and public reception of African American literature in the heart of the twentieth century.

Few institutions seem more opposed than African American literature and J. Edgar Hoover's white-bread Federal Bureau of Investigation. But behind the scenes the FBI's hostility to black protest was energized by fear of and respect for black writing. Drawing on thousands of pages of recently released FBI files, William J. Maxwell’s book F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature exposes the Bureau's intimate policing of five decades of African American poems, plays, essays, and novels. Starting in 1919, year one of Harlem's renaissance and Hoover's career at the Bureau, secretive FBI "ghostreaders" monitored the latest developments in African American letters. By the time of Hoover's death in 1972, these ghostreaders knew enough to simulate a sinister black literature of their own. The official aim behind the Bureau's close reading was to anticipate political unrest. Yet, as F.B. Eyes reveals, FBI surveillance came to influence the creation and public reception of African American literature in the heart of the twentieth century.

The F.B. Eyes Digital Archive makes available for the first time a collection of 51 FBI files on prominent African American authors and literary institutions, many of them unearthed through William J. Maxwell's Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Now part of the public domain as unrestricted U.S. government documents, these once-secret files are arranged on this site as they were at FBI national headquarters, under the names of individual authors and institutions.

The collected files of the authors alone comprise 14,289 pages, or the rough equivalent of forty-seven substantial PhD theses. If this seems a strange comparison, it should be noted that the average length of the 46 author files reaches above 300 pages. FBI ghostreaders genuinely rivaled the productivity, if not always the insight, of their academic peers. The Bureau’s copious files addressing twentieth-century African American writing are documents of troubling state surveillance and sometimes-illegal counterintelligence. But they are also recognizably literary-critical documents, analytical encounters that cannot always resist the pleasures of the enemy text.

More detailed information on the contents of the files and on the means used to collect them can be found in the introduction to F.B. Eyes: http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i10321.pdf.

William J. Maxwell is a professor of English and African and African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, where he teaches modern American and African American literature. He is the author of New Negro, Old Left: African American Writing and Communism between the Wars and the editor of Claude McKay's Complete Poems. He can be reached at wmaxwell@wustl.edu.

F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover's Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature is published and distributed by Princeton University Press: http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10321.html.

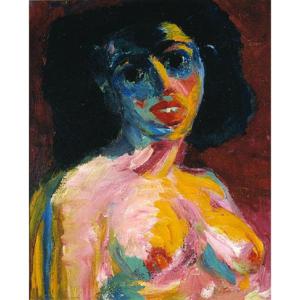

Facing Despair: Expressionist Portraiture in Wartime

Expressionism, reliant as it is upon the subjective emotional approach of the artist, has a powerful ability to reflect the circumstances of the world around the artist. Portraiture in particular shows the emotional response of both the subject and artist to their particular personal and historical contexts. As a movement, Expressionism had reached its peak in influence and popularity during the pre-World War I and interwar years, and many of its main practitioners were in the later stages of their careers by the time Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933. In the late 1930s, many German Expressionists, such as Max Beckmann, were forced to flee Germany due to Nazi persecution. Expressionists working elsewhere in Europe, like Georges Rouault and Paul Klee, were also overwhelmed by the specter of war and Fascism that haunted Europe during that time period. This exhibition will explore the portraiture of these three artists—Beckmann, Rouault, and Klee—on the cusp of the breakout of World War II.

Professionally, these artists had achieved fame and success for their contributions to Expressionism long before World War II. But the rise of Nazism jeopardized their place in European culture and society and threatened the forms of expression that they had worked with throughout their careers. Though always dealing with fraught, subjective, and deeply personal subject matter, the prospect of devastating war and the muzzling effect of totalitarianism permeated both the subject matter and the emotional underpinnings of the artists’ work. Though they had lived through and been deeply affected by the horrors of World War I, the rise of Nazism threatened their style of expression in new and terrifying ways. They used techniques they had been using for years but now applied them to much darker themes and experiences.

While they have common themes like numbness, isolation, darkness, and dread, the works are also a study in contrasts. Klee would die in 1940, and his The Man of Confusion shows a fearful, isolated figure floating in undefined ether, reflective of the emotions of a dying man in uncertain, frightening times. Rouault’s Chinois was part of a series of works called “Miserere et Guerre” (“Misery and War”) that dealt with the emotions of the individual in suffering and strife, heavily influenced by the artist’s Christian faith. The last work is Beckmann’s Acrobat on Trapeze,which he painted while in exile in Amsterdam in 1940 after fleeing Nazi persecution and the label of “degenerate.” The figure of the acrobat, long a source of inspiration for Beckmann’s work, is represented as a reclusive, shadowy figure who is entirely removed emotionally from the adoring crowds below—a reflection of Beckmann’s state of mind in exile. Together, these paintings show the attempt of these Expressionists to communicate the melancholy experience of the individual in a continent on the precipice of immense human disaster, on the grand scale and for the individual.

Higher Ground: Honoring Washington Park Cemetery, Its People and Place

The history of Washington Park Cemetery reveals within its microcosm of events, a complicated tangle of social injustice, racial politics, and imbalance of power.

Washington Park Cemetery, located near Lambert St Louis Airport in the city of Berkley, MO was established in 1920 as a burial ground for African Americans at a time when rigid segregation was common practice. For nearly 70 years, it was the largest black cemetery in the region, the final resting place for many prominent African Americans as well as lesser well-known citizens. The cemetery’s long and tragic history reveals a complicated tangle of social injustice, racial politics, imbalance of power, and dismal neglect.

On three notable occasions, the peace of the grounds was disturbed: first in the late 1950’s with the construction of Interstate 70, in 1972 when Lambert Airport acquired nine acres for its use, and again in 1992 when bodies were disinterred to make way for the Airport runway expansion and MetroLink’s extension to the airport.

This exhibition is in part protest, in part tribute, and in part, historical documentation. The work offers an effort and a promise toward acknowledging the cultural and historical significance of Washington Park Cemetery, and toward honoring the people touched by decades of oversight, neglect, and disruption.

In Character: The Life and Legacy of Mary Wickes

This site is a digital companion to an in-person exhibit that appeared in the Main Lobby and Gingko Room from October 2013 to March 2014. The items in this exhibit are from the Mary Wickes Papers and other collections housed in the University Archives collection. Our archive is comprised from more than 300 unique collections, chronicling the history of Saint Louis. Please visit our website to learn more about our collection. Please go to the introduction to start exploring this exhibit.

Independence in the City

Expressionism was a radical departure from European artistic standards. The artists didn’t strive for realism, but rather a more expressive and subjective treatment of their surroundings. Through their brash use of color, gesture, and form, they conveyed an emotional understanding of their subject matter. With this strong focus on emotion, came a more individualized approach to making art. In Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s painting View from the Window, 1914, Emil Nolde’s lithograph A Church by a Harbor, 1907, and Ludwig Meidner’s two-sided painting Burning City, 1913, this individuality can be seen in their distinctive treatment of their urban environments. All three artists held a similar distaste for their surroundings. This was a motivating factor behind each of the works at hand. With their like subject matter, the different ways in which these three approach their work becomes especially apparent. The aggressive distortion present in each cityscape was a means for the artist to channel past experiences and portray their unique mental state.

In seeing how these works represent the artists as individuals, it is also necessary understand to how they fit into the larger context of German Expressionism. These artists were all working at a similar time and often in close proximity. Nolde and Kirchner were both affiliated with The Bridge, a group of German artists active from 1905 to 1913. The stylistic tendencies of the group were similar to that of the Fauves with a use of pure color and a break from illusionistic tendencies. They shared a strong collaborative spirit, even living together and shared studio space.

Nolde was only a member of the group for a brief period of time. Being much older, he found himself unsuited for the artists’ colony and left in 1907, only a year after he had joined. Despite his short stay, it did have a large influence on his work. It made him work to create a more individualized style, with bold color and an expressive treatment of form. This influence can be seen in A Church by a Harbor, 1907, a work he made during this short period. Its distinct use of gesture and expressive use of the lithographic medium are likely resultant of his collaboration with the members of The Bridge.

Six years later, in 1913, The Bridge disbanded and Kirchner painted View from the Window. In the wake of this he searched to create a more individualized style. Unlike Nolde who was responding to the aesthetic of the group, Kirchner was attempting to distance himself from it. He balanced a number of outside influences, like his interest in German artistic tradition, with a need for self-expression. In View from the Window this can be seen in his distinct treatment of space and line. He was shifting his focus to a more modern subject matter, the city, and creating a style to match.

In contrast Meidner stayed largely independent, not joining artist groups like The Bridge or The Blue Rider. Although their influence can be seen in his work, his visual and conceptual framework was based more on introspection. This separation has a clear presence in the three works shown. Burning City seems to stand in opposition to the other works because of its violent energy. While Kirchner and Nolde were painting their surroundings, Meidner creates a totally imagined scene. This painting can be seen as precursor to the second wave of Expressionism, where artists turned away from an individual retreat to something more didactic and relevant to the real world. The scene of destruction Meidner creates has a strong moralizing tone, with a message in direct response to urbanity.

Within German Expressionism these works represent a range of circumstances: Nolde’s time with The Bridge, Kirchner’s newfound independence, and Meidner’s total autonomy. Understanding these circumstances is important in examining their representation of the city, but moving past this historical lens is also necessary. For each artist his treatment of the city was a projection of self. These works represent each artist more as an individual than they do the collective whole of German Expressionism.